Christ in the Clutter: Notre Dame Then and Now

- BRAD MINER

Watching the spillover crowd in Notre Dame de Paris at the Sunday evening vigil for the victims of the terrorist attack was a moving experience.

It's amazing how a brush with evil can turn people towards God. But it reminded me of a long ago personal experience, which also led to a deep spiritual turn.

It's amazing how a brush with evil can turn people towards God. But it reminded me of a long ago personal experience, which also led to a deep spiritual turn.

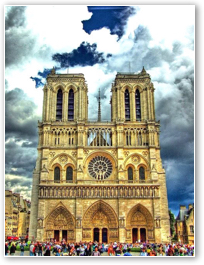

One August day in 1968, I went ambling alone along the streets of Paris. I had a cheap hotel room in the Saint Germain area, and I took my time sauntering over to and across the Pont Neuf to the Île de la Cité and Notre Dame.

At that point in my life, I was a pagan college kid, and I'd been inside just two Catholic churches, both in Ohio: one in my neighborhood for the mysterious First Communion of an elementary-school classmate, pretty in her white dress and mantilla — that was pre-Vatican II; the other just a few months before — at a Mass my Catholic girlfriend took me to, held in a Quonset hut that was the temporary parish church on campus. In neither case had I paid the least attention to what was going on. It was just about the girls.

The candles and statuary and crucifixes inside Our Lady of Paris — the sheer foreignness of it all — offended me, for I was used to the shark-like simplicity of the Methodist church of my youth, although I was, as a pagan would be, utterly indifferent to facile Protestant piety. Yes, I thought, Notre Dame is interesting architecturally, but it's too ornate. How could you find God in all this clutter, if there were a God to find?

But there was something else, and I knew it. I'd read that the Gothic arches of the interior were meant to represent praying hands, and there were a lot of people kneeling and praying in the cathedral with eyes upraised, and there was everywhere. . .a feeling of awe. I felt it. There were hundreds of people milling about in silence. Had I been with friends — my Buckeye buddies — we'd be standing there, I knew, as still and silent as everybody else, with none of the irreverent hijinks that otherwise practically defined us. Alone (no backs to slap), I began to be unsettled by this awe. Never had I felt so small. As the distress in me rose, I spoke one word in anxious recognition, almost as a charm against the mystery: Jesus.

I turned to leave and saw the south transept's Rose Window for the first time, noonday sun streaming through it — the sound of a Mass just beginning behind me — Mary with the baby Jesus up there in the center of it all, the stained-glass and its eighty-four panes, a dizzying kaleidoscope of Apostles and angels and the Resurrection and Hell.

I fled out to the Place du Parvis (now, Place Jean-Paul II), feeling the gargoyles ogling me as I hightailed it back to the Left Bank.

On a train to Rome a few days later, I got to wondering about my reaction. I didn't believe in God, and I thought the Roman Catholic Church was a giant, delusional pyramid scheme, although I'd been quite taken with the survey of Europe in Western Civ 101 and 102, in which the Church had loomed so large. But in an essay (for which I'd received an A-minus) I'd lashed out against Catholicism over the treatment of Galileo, and my professor had scribbled in the margin, "This would have been an A+ were it not for your anti-Catholic outburst. Try being objective all the time." When I later told him I was headed off to Europe in the summer, he gave me a kind of penance: he made me promise to visit all the major cathedrals in Paris, Rome, Florence, Vienna, and Prague, although he doubted — my plans notwithstanding — that I'd be able to get into Czechoslovakia. (He was right. Two days before I was scheduled to travel from Vienna to Prague, 2000 Soviet tanks and 200,000 Warsaw Pact troops invaded.)

That summer was, in my mind, my emancipation from all past restraints, and I had no sense at all that God was binding me to the very object of my disdain.

But as the Paris train rolled south towards Rome, I meditated on the power of history and literature to capture your imagination, to get under your skin, even though you told yourself it had nothing to do with you. That summer was, in my mind, my emancipation from all past restraints, and I had no sense at all that God was binding me to the very object of my disdain.

In Italy, I dutifully went into St. Peter's, and then to Il Duomo in Florence, and in Vienna I went to Stephansdom. On a stopover in Lausanne, Switzerland, I even went running to the hilltop Cathedral of Notre Dame, which you can see from the city below (and which a passerby had identified for me by name), only to discover it had apostatized in the 1500s. I had absolutely no reason to be disappointed by that, but I was.

Back in Paris I returned to Notre Dame. The aroma of a Catholic cathedral is unique, nothing like the pine-fresh scents of Midwestern Protestantism, and I sat in a pew in what I still consider the greatest church in Christendom and tried to break it down: melting wax, incense, sweat, tears, sighs, age (whatever that means: grime, mold, mildew?) . . . Now instead of "ornate" the word that came wafting to mind was "ancient." I remember thinking: What's old is new.

Jean-Charles, the desk clerk, recruited me to have dinner with him and two young women who were guests in the hotel: he was smitten with Ilke, a German girl, which left me with a dark-haired Mexican lovely named María, who spoke not a word of either English or French. She wore what I called, complimenting on its beauty, a silver cross. Through Ilke's translation (she spoke English, Spanish, and French in addition to German), María corrected me: "It's a crucifix."

I stand corrected.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Brad Miner. "Christ in the Clutter: Notre Dame Then and Now ." The Catholic Thing (November 18, 2015).

Brad Miner. "Christ in the Clutter: Notre Dame Then and Now ." The Catholic Thing (November 18, 2015).

Reprinted with permission from The Catholic Thing. All rights reserved. For reprint rights, write to: info@thecatholicthing.org.

The Author

Brad Miner is the Senior Editor of The Catholic Thing and a Senior Fellow of the Faith & Reason Institute. He is a former Literary Editor of National Review. His most recent book, Sons of St. Patrick, written with George J. Marlin, is now on sale. His The Compleat Gentleman is now available in a third, revised edition from Regnery Gateway and is also available in an Audible audio edition (read by Bob Souer). Mr. Miner has served as a board member of Aid to the Church In Need USA and also on the Selective Service System draft board in Westchester County, NY.

Brad Miner is the Senior Editor of The Catholic Thing and a Senior Fellow of the Faith & Reason Institute. He is a former Literary Editor of National Review. His most recent book, Sons of St. Patrick, written with George J. Marlin, is now on sale. His The Compleat Gentleman is now available in a third, revised edition from Regnery Gateway and is also available in an Audible audio edition (read by Bob Souer). Mr. Miner has served as a board member of Aid to the Church In Need USA and also on the Selective Service System draft board in Westchester County, NY.