Knowledge, Virtue, and Holiness

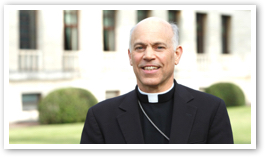

- ARCHBISHOP SALVATORE CORDILEONE

Our Catholic schools exist to serve the Church's mission of sanctification and evangelization.

I. Introduction

In his first Encyclical, Lumen fidei ("The Light of Faith"), Pope Francis begins with the following words:

In his first Encyclical, Lumen fidei ("The Light of Faith"), Pope Francis begins with the following words:

The light of Faith: this is how the Church's tradition speaks of the great gift brought by Jesus. In John's Gospel, Christ says of himself: 'I have come as light into the world, that whoever believes in me may not remain in darkness' (Jn 12:46)…. To Martha, weeping for the death of her brother Lazarus, Jesus said: Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?' (Jn 11:40). Those who believe, see; they see with a light that illumines their entire journey, for it comes from the risen Christ, the morning star which never sets.

The students in our Catholic schools are at the beginning of their journey of life, and it is your privilege, as their teachers, to accompany them at this critical stage of their life's journey, a stage that for many of them will determine the trajectory of their entire life. This teaching from so early on in Pope Francis' Petrine ministry clearly reflects the emphasis he places on the theology of accompaniment; it also, I believe, gives a helpful definition to what our Catholic schools are called to do: journey with our young people out of the darkness into the light of the risen Christ.

While they may not think of it in exactly this way, parents do entrust their children to Catholic schools with the expectation that our schools will form and inform their children as well as shield them from harm. I am grateful to you for all you do to help illuminate, order, and sanctify the lives of the teenagers entrusted to your care. In addition to presenting material to them in the classroom, you coach them in making sense out of their experiences in the Church and in our modern culture. Students look to you for guidance. Although as freshmen and sophomores they may be reticent to think deeply, you encourage them and lead them on, and eventually most students do desire to think critically. But they also want to understand life, which poses many conundrums to them. The students listen to you and watch you for guidance. Many of you have an impact on their lives that is humbling to you. I am grateful for your service and I pray that students indeed listen to you and imitate the fundamental human and religious qualities you share with them. Like many of you, I, too, can think back to teachers in my high school who have had a lifelong effect on me, and one in particular — and not because of what he taught (although yes, he was a great band director), but because of the kind of person he was and the values he modeled to us in word and deed.

And like me, I'm sure many, if not all, of you also have wonderful memories of your teenage years. Those are years filled with wonder, or at least they are meant to be: discovering new friends and new activities, testing our limits and the limits imposed on us, with all of the successes and failures that involves, and sometimes doing dumb and even dangerous things, morally as well as physically, and then receiving the punishment that goes with it. But thank God for parents' admonitions, for honest evaluations by teachers, coaches and moderators, and for the help given by the Church and the Holy Spirit.

My subsequent comments take this enchanted high school world for granted. Our hopes and prayers are that teenagers grow in wisdom, age and grace during the four years they are entrusted to us. The culture of a Catholic high school is both challenging and reassuring for students and teachers. Teachers confront difficult challenges, but most teachers accept all the trials and disappointments with good humor, because they are delighted to be in the presence of happy, lively students. At the same time, many students at this age need big injections of intellectual curiosity. Challenges there are, but the delights and satisfactions are also abundant.

Teachers enjoy the challenge of teaching students and getting them to think on their own, to think critically about the human condition, and to think carefully about the role their Catholic faith actually plays and ought to play in their lives. A crucial challenge for Catholic high schools is striking the correct balance between fostering careful reasoning and promoting Catholic faith and practice. A Catholic school should also offer students clear ideas of what constitutes human excellence and success.

II. The Mission of Catholic Schools

Catholic high schools enjoy a solid reputation as excellent institutions of education and formation. Experience highlights three factors in particular that contribute to overall success of Catholic high schools. The first factor is high academic expectations for all students, no matter what their cultural, linguistic or ethnic background. The second factor is that Catholic schools teach young people to apprehend truth using both faith and reason. We know from our Catholic tradition that both are necessary: each must make its unique contribution that only it can make, and serve as a check on the other lest knowledge be reduced to simple pious platitudes on the one hand or, on the other, superficial or self-serving assertions that cannot see beyond the material world. The third factor is that principals and presidents at Catholic high schools seek to hire teachers who are interested in being involved with students outside the classroom. As coaches, moderators or facilitators of different events at the school, these teachers share their hopes and skills with the students in a more personal way. This has a significant impact on students.

The three factors — high academic expectations, faith and reason, and teachers interacting with students both in and outside the classroom — contribute to building a Catholic worldview. All of this, of course, must be reflected in the school's mission statement. Catholic schools have mission statements that focus on these factors and what the goal of Catholic education is. Mission statements that are clear and compelling help students, faculty, staff and parents alike to know that they are working in a Catholic educational environment and to understand what that means.

In what has become by now a classic phrase in the world of Catholic education, Catholic schools help students to excel in life because of our understanding of what our schools are all about: education of the whole person. As we know from science, philosophy and our Catholic faith, the whole person, especially the whole person redeemed by the Incarnation, Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, is wonderfully complex. The root meaning of the word "educate" is "to lead out from." That is, a Catholic education draws out all the potential in the whole person of every student, leading the student to true human flourishing and thus becoming the person God has created them to be.

As the Fathers of the Church emphasized, human potential increased greatly with the coming of Christ, the New Adam. By being baptized in Christ Jesus, Christians participate in the divine life of Christ. Because of this, every Christian has the calling to be holy — certainly one of the truths of our faith emphasized at the Second Vatican Council. A Christian — teenager or adult — is expected to use all the means available to them to fulfill this vocation common to every Christian.

So the challenge is a complex one. The whole person involves the intellectual, physical, emotional, social, moral and spiritual dimensions of each student. A Catholic high school is certainly an educational institution, but it is also has the charge of instilling in its students morality and growth toward holiness. God speaks directly and indirectly to students through the moral challenges they face, through prayer, through study, and in the sacraments.

Even though the focus is on the education of the whole person, this occurs in the context of a community, the high school itself. Similarly, holiness for the student is achieved by working within the Church, which is what Jesus preached when he spoke about the Kingdom of God. Full flourishing of the human individual occurs through participation in the life of the Church.

III. True Success

Accrediting groups for grade schools, high schools, and colleges and universities now all focus on assessment. They want these institutions to assess what they judge to be the most important goals in light of their mission statement and perhaps vision statement. The goal of Catholic schools can be expressed as the full flourishing of the human person. By reason of our belief in Jesus Christ and the Church he founded, this has to include outstanding service in the Church.

The two main activities of the Church are the sanctification of people already members of the Church and drawing others to belief in Christ, that is, fulfilling the "Great Commission": "Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you" (Mt 28:19). This is all for the sake of leading individuals to attain the fullness of their human potential, which can only occur when one joins one's will to God's will.

Our Catholic schools exist to serve the Church's mission of sanctification and evangelization. This mission indicates that some widely esteemed achievements in secular society are inadequate goals — not in themselves contrary, but inadequate — for Catholic youth. They become goals contrary to the Catholic mission of a school if they become separated from the call to holiness and the mission to evangelize.

This means that Catholic educators will look at secular achievements in a different way: under the light of faith, that is to say, with a view to the spiritual, transcendent dimension of the human person.

Graduates of our schools are to be congratulated for securing admission to prestigious four-year universities, because this is something good in itself and a sign that a student is realizing his or her full potential. However, if, for example, one of our alumni graduates from such a prestigious institution and goes on to become the CEO of a multi-national corporation but has stopped practicing the faith, runs an unethical corporation, or has jumped in and out of numerous relationships and brought children into the world out of wedlock and doesn't give the care and attention a child needs and deserves from parents, a Catholic educator would look on such a situation as a disappointment. On the other hand, if, say, a student graduates from one of our schools and decides to marry earlier in life rather than later, works responsibly in a blue-collar job, centers their life around their marriage and children, the family remains strong in the practice of the faith and the parents successfully hand on that faith to their children by creating a happy, loving home for them — this is what any Catholic educator should deem a success. The core issue, then, is what counts as true success in life.

In the end, our Catholic schools exist to help young people attain holiness in their lives, that is, to become saints. An outstanding career is not a sign of having reached or even drawn near to the goal. Holiness is extraordinary, but it is usually achieved in ordinary circumstances. The first place in which that happens is in the context of one's vocation. Fidelity and perseverance in one's vocation is a sign of growth in holiness. We speak of the four traditional vocations in the Church: marriage, priesthood, religious life and single life in the world. But vocation also carries with it the sense of using one's talents — especially any extraordinary talents that God may have given — for the service of God in the work that one does. In this sense, one's career can be part of that vocation, but not simply measured by material success. I'm sure many of you feel your life as a teacher is not simply a profession but a vocation: you cannot be true to yourself if you do not teach, and so you give yourselves generously to your students through sharing your time and talent with them. It places demands on you, it requires sacrifice, and you could be making more money doing something else with your talents, but you experience blessings from God in return that are beyond material measurement. This is also part of what it means to be faithful and persevering in one's vocation, leading to growth in holiness.

Holiness also stems from participation and service in the life of the Church, which for the vast majority of our people means in their parish. It is in the parish where one is formed in the faith: where one learns evermore the truth of Jesus Christ as it has been handed down and developed in the Church, where one worships and serves with one's fellow parishioners, where one is sanctified by the grace of the sacraments — all of this, so that parishioners can then go forth and spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ in the various communities in which they interact. So, immersion in the life of a parish is also a sign of growth in holiness.

IV. The Hard Parts

I think we all feel inspired when we hear the noble call from our Church leaders to our Catholic schools to be places where young people can attain their full potential, that they have the mission to help our young people become saints. Of course, our students' growth in faith happens primarily in their families since — as another principle of Catholic education tells us — parents are the first educators of their children. But Catholic schools also play a central role in our students' formation in their Catholic identity, and teachers contribute significantly to their students' growth in their Catholic faith. As inspiring and lofty as this may all sound, though, to respond to this call with integrity requires a lot of heavy lifting, because there are a lot of hard parts involved with it. That is to say, promoting the faith in our contemporary society is difficult primarily because the ambient culture either explicitly or implicitly promotes secular values that often run counter to Catholic values, or at times do not align well with them. For this reason, in order to live a faithful Catholic life nowadays one needs to be very intentional, even to the point of developing a very deliberate strategy, so as to counteract the impact of secular society on our students.

A. Instilling Virtue

Earlier in this talk I referred to holiness and indicated that holiness occurs within the community of the Church. That is the context. It is only together, as members of the Body of Christ that is the Church under him as our head, that we journey under the light of faith so that, believing, we can see the good that lies beyond this material world and attain it. This is holiness.

In undertaking the examination of the cause of canonization of a proposed saint, the promoters of the cause must prove that the servant of God demonstrated "heroic virtue." This is the definition of holiness, heroic virtue, that is, a very high standard of consistently acting to realize human goods. Anything involving growth, though, means one starts at a lower level and moves to a higher level. Young people must first acquire a basic level of virtue before they can move on to practice heroic virtue in their lives. In order for our schools to be successful, to fulfill their mission on behalf of the young people they serve, our schools must instill within them a life of virtue.

B. Starting at the Foundation

Our young people need to acquire and master many virtues in order to navigate well the perilous waters of life in the world today. Some virtues are foundational, in the sense that one must acquire them in order to excel in other virtues that build upon them. Such virtues may also be basic in the sense that they are necessary for good Christian living. Loving God and neighbor means one gives to God and others not in order to get things from the Almighty or from one's kind and generous neighbor, but simply because one loves God or desires the good of another person. Christian giving is giving in order to give, not to get. Giving is how God made us to find happiness, and when we live that way it pleases God. Teenagers, in particular, need constant encouragement to practice such virtues at home, in school and in their social activities. I would like to point out, though, two virtues in particular that our schools especially have to focus on, both because they are foundational and because they are virtues which contemporary culture either does not support or outright disparages in a very aggressive way.

1. Humility

The mystics all tell us that the necessary first virtue on the path to holiness is humility. Already we have a huge challenge: it means counteracting the entitlement mentality so prevalent today. Our young people are bombarded with the message that to achieve their dreams they have to believe in themselves. We know, though, that this type of blind promotion of the individual gets students off on the wrong foot. From 4,000 years of saints and scholars reflecting on the truth revealed from God and experiencing the work of God's grace in their lives, going back to our Jewish ancestors in the faith, we know that to attain true human flourishing one must begin by believing in God. One must also know who one is before God, and to know what God is calling them to do with their life so that they may serve God.

Modern society belittles the virtue of humility. In our entrepreneurial society, especially here in San Francisco, practitioners of humility are "nice guys who finish last." Correctly understood, however, humility is a virtue based on reality, on the way things are. "Humility" comes from the Latin word "humus," which means "earth." Humility means lowliness, as in being close to the earth. But the earth is the ground upon which we walk, so humility is what grounds us in reality, so that we can walk successfully through the many vicissitudes of life. Humility means that we realistically account for where we are now and where we are going. This is the most startling way in which humility is fundamental. If we lose track of our basic reality or where we are heading, whatever happens down the line may be disastrous, even though in the eyes of the world we may seem to have made great progress materially.

The virtue of humility is a Christian virtue based on the reality of a finite person, made by God in the image and likeness of Infinite Being. God instills in human nature a desire to seek and respect the basic goals of human existence. Respecting basic human goods means one conforms to norms, objective norms which exist as givens in the created order. This is also referred to as the natural law. According to these norms, certain human goods must always be respected: life, truth, beauty, love, friendship, and others as well. These are general goals for all humans. Particular goals get sorted out in prayer, which is conversation with God. As the young person matures, he or she gains more skills, experiences and insights. A humble person approaches God in prayer and asks: "Lord, what do you want me to do?" This is the question every young person must ask themselves in order to discern their vocation, and it is incumbent to our Catholic schools to assist them in doing so and in finding the answer.

The reality is that humans are made by God to love, praise and honor Him in this life and be happy with Him in the next. The virtue of humility is the regular disposition and practice by which a person acknowledges his or her true defects and gifts, and in light of those, submits to God's will and to the good of others for God's sake. That is, the person accepts the fundamental reality of both imperfection and God inviting the person to use his or her gifts to praise God and serve others.

A saying attributed to St. Augustine is that "humility is the foundation of all other virtues; hence, in the soul in which this virtue does not exist, there cannot be any other virtue except in mere appearance." And in her Autobiography, St. Teresa of Avila says "there is more value in a little study of humility and in a single act of it than in all the knowledge in the world" (chap. XV).

Teachers are in the truth business. They impart truth to students, help students to discover the truth, and teach them skills in how to evaluate whether something is true or simply an erroneous view shared by some people. Catholic teaching is that Jesus Christ is the Way, the Truth and the Life. This means that the Bible and the truth in Christ are compatible with truth in the sciences and the humanities. This is faith and reason working together, leading one ever more fully into the light of Christ. A Catholic school relies on its teachers to share basic Catholic insights concerning truth with students, in order to accompany their students on the path of discovering, appreciating and appropriating the truth. As all teachers realize, sharing a conviction occurs in two ways: one can verbally state what one's convictions are or, by one's actions, one can demonstrate what one's convictions are.

Because a teacher is in the classroom with his or her students every day, this constant student exposure to the thoughts and convictions of the teachers allows students to figure out, at least in some areas, whether a teacher's verbal convictions are also reflected in the actions of the teacher. It is the great call of teachers to teach and practice humility in the classroom in the fundamental sense that I have laid out here. As I have portrayed it, the truly humble person has three convictions. It begins with the response Pope Francis gave in the interview published in America magazine when he was asked, "Who is Pope Francis?" True to his Ignatian charism as a Jesuit, he responded, "I am a sinner." This is the start, the first conviction. But it is seen in the light of the second conviction, namely that I am made in the image and likeness of God, and therefore I recognize both faults and gifts within me. And third, I strive to fulfill God's plan for me.

Teachers might reasonably object that, if that is all teachers accomplish in Catholic high schools, it does not yet yield many results for students. True, humility by itself is not enough. However, without helping students practice the virtue of humility, that is, the three convictions I just mentioned, we leave out the most important foundation for all learning. So, humility alone is insufficient, but without it, learning is impossible. And not only learning, but every other human and theological virtue, including the one for which everyone is yearning in the deepest core of their being, and so often search for in the wrong places: love.

The narcissistic obsession with the cult of self we are now witnessing in the culture is, I believe, a symptom of a very deep insecurity and loneliness in our society. People are yearning for love, intimacy and companionship, yet very often fail to attain it. It is clearly true that many people are incapable of, or at least not disposed toward, persevering in a committed relationship in their life.

2. Chastity

Which leads us to the other foundational virtue, the one which more than any other is abhorred by the contemporary culture and so the one where we find the greatest challenge of all to instill: chastity.

While many people do not value humility as a virtue, they will at least respect someone who is humble even if they don't aspire to emulate the person. When it comes to chastity, though, most people see it as a purely a negative thing, a deprivation, giving up something they intensely desire for no payback at all, nothing more than a suppression of the sexual appetite. Furthermore, if people think of chastity at all, most people think it applies primarily to young people and unmarried people. In fact, chastity is a virtue for every age and every state in life.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines chastity as "the successful integration of sexuality within the person and thus the inner unity of man in his bodily and spiritual being" (n. 2337). Another way to put it is that chastity is the constant disposition to love another person the way that person should be loved, corresponding to the person's intrinsic human dignity. This takes us far beyond the very superficial understanding of chastity which sees it as simply "no sex outside of marriage." Certainly observance of this moral norm is absolutely necessary for one to be chaste, but by itself this is insufficient for acquiring the virtue of chastity in all its fullness.

In mentioning the word "sex" a moment ago, I used it in the very colloquial sense so often used today as a euphemism for sexual intercourse. But I would like to point out here a helpful linguistic point that has been made by an excellent Catholic writer, Anthony Esolen. He recommends that, instead of referring to sexual intercourse in shorthand manner as "sex," we refer to it as the "marriage act" (I have also heard people refer to it as the "marital embrace"). The marriage act is an accurate statement of what sexual intercourse entails, at the very least from a Christian point of view. It is the complementary and comprehensive union — physical, emotional and spiritual — of two people who are publicly committed to each other for life and desire to raise and love whatever children proceed from their marriage acts.

An advantage of Esolen's language is that one does not speak of pre-marital sex, precisely because the marriage act is situated in marriage. Rather, one would have to speak of the marriage act outside of marriage, and this very formula highlights the contradiction. Esolen's linguistic point underscores the deeper meaning of chastity: the constant disposition to love another person as that person should be loved, which applies equally to married couples as to those who are not married. The obvious question, though, immediately arises: What is the true meaning of love?

Given the distorted and demeaning answers to this question we find all around us these days, creating enormous confusion in the minds of many people, we have a huge challenge before us. So when I do confirmations, I sometimes ask the confirmandi precisely this question: What, really, is love? After the usual long, uncomfortable silence as I wait for someone to raise their hand (that even happens when I ask questions that I know they know the answer to!), I answer for them by pointing to a crucifix. When you say, "I love you," you are saying, "I am willing to give everything for you, to give up all of my selfish habits in order to please you, even to the point of giving up my life for you." Love, then, is the giving of oneself to the other for the good of the other. It means respecting and affirming the intrinsic dignity of the other at all times and in every way, and never treating the other as a means to an end, as a way of getting some benefit you are looking for, even unconsciously.

Chastity as genuine love (not merely physical attraction) for another person stresses the person's willingness to extend oneself to the utmost limits to do things that are for the good of another person. A necessary characteristic to act always with this motivation is that one must be selfless. But one also has to understand that some acts, such as the marriage act, have attractive qualities, but only work for the good of the other person, including the offspring, when they are performed in the context of marriage.

Chastity is also obviously central to the vocation of priesthood and religious life. Also in these cases, candidates for these two vocations have to integrate well their sexuality with their interior life. If this does not occur, the priest, nun or brother will not be able to interact well with other people.

We certainly want to encourage among students vocations to be priests and religious. But most of them will be called to marriage, and marital chastity is equally central to a couple's happiness and perseverance in their vocation. Our young people will simply not find true, deep happiness in life if they do not acquire the virtue of chastity. I would say, then, that one barometer that could be used for gauging a young person's prospects for attaining true, deep happiness in life and perseverance and success in their vocation is their capacity for fidelity in marriage, regardless of what their vocation is.

Chastity, then, together with humility (without which chastity — and all other virtues — is impossible) is what enables a person to live beyond a mere superficial, banal existence to one which is other-centered and open to the transcendent; it enables one to look beyond the surface, beyond the physical, to the other's interior life. And it lives these deep human goods in very concrete ways, in the body.

Fortunately, teachers have many opportunities in the classroom to emphasize the importance of considering the entire person, the sexuality of the person united and integrated into the spiritual and interior life of the individual. Obviously religion, but also in the area of literature, history, biology, modern language, and even the physical sciences, this topic can be addressed from a number of perspectives.

IV. Practical Applications

I have emphasized the importance of the virtues of humility and chastity for two reasons. First, these are essential for complete human happiness and satisfaction. They are not optional acquisitions, and the earlier students acquire these virtues the more effective and satisfied they will be. But the second reason for the emphasis on humility and chastity is that Catholic high schools, with few exceptions, are the only schools that attend to training their students in these virtues. Unlike most other schools, this is part and parcel of what Catholic schools are all about.

This most certainly is not to say that other virtues are unimportant, let alone optional. No, no, no, absolutely not. We need to help our young people grow in all of the virtues: the theological, cardinal, and moral virtues. Humility and chastity are the virtues upon which to build. Some of the other virtues, yes, are esteemed in the secular culture, but without a Christian perspective they can easily become self-serving. Take, for example, the virtue of charity. Yes, of course, it is absolutely essential that our young people graduate from our schools well-formed in the virtue of charity. But they also have to understand what that really means. It is not simply giving some of your extra time, talent or treasure to someone in need, and then go on with your life unchanged. Again, Christians give to give, because that is how God made us to be and that is what pleases God. Charity is love in action, the love of agape. It involves a very human encounter in which both come back changed. Pope Benedict XVI has a wonderful reflection on this in his first Encyclical, "God is Love":

Practical activity will always be insufficient, unless it visibly expresses a love for the human person, a love nourished by an encounter with Christ. My deep personal sharing in the needs and sufferings of others becomes a sharing of my very self with them: if my gift is not to prove a source of humiliation, I must give to others not only something that is my own, but my very self; I must be personally present in my gift [DCE, n. 34].

This is love in action that affirms the dignity of the other as an intrinsic good.

The times we live in pose very drastic challenges to us for teaching all of the virtues properly. The temptation we all feel is to soft-pedal these issues — better not to go there, or at least don't insist upon it, less we be judged adversely by others and not "fit in." But this is a time more than ever that our Catholic schools have to step up to the plate, and be true to what they are called to be — for the good of our young people in this life and in the next.

But these virtues also serve the good of society as a whole. Earlier this week I attended a conference on bioethical issues under the theme of Pope Francis' theology of accompaniment. One of the speakers was Alana Newman, a young lady who was the product of IVF. She spoke about the personal harm she suffered not knowing who her biological father was — or as he is considered, who her "sperm donor" was — and all that she tried to do to track him down to know her connection to her heritage, how she had self-destructive tendencies and felt that she had no value. She also spoke about the negative consequences to society when fathers become disposable, which, as we know, happens in a whole lot of other ways as well. In addition to drastically increased risk of teen pregnancy and divorce for girls who come from a fatherless home, these are some of the statistics she cited:

90% of homeless and runaway youth come from fatherless homes.

90% of adolescent repeat arsonists live with only their mother.

80% of rapists come from fatherless homes.

75% of adolescents in chemical abuse centers come from fatherless homes.

Lately Pope Francis has also been emphasizing the importance of the role of the father in the family. In his general audience just two days ago, he had this to say:

The first need, then, is precisely this: that the father be present in the family. That he be close to his wife, to share everything with her, joys and pains, difficulties and hopes. And that he be close to his children as they grow up: when they play and when they pursue their interests, when they are careless and when they are distressed, when they talk and when they are quiet, when they are bold and when they are afraid, when they make a mistake and when they recover from it; the father must always be present, always.

It is because of the foundational value of both humility and chastity, and the especially serious challenges we face in teaching these virtues, that they played a role in my decision to clarify what the Catholic archdiocesan high schools stand for. As you know, I have made proposals to the union to add language in the Collective Bargaining Agreement that clarifies the role of Catholic schools. In a related issue, I have asked the presidents to include in the Faculty Handbook statements that the institution, that is, each archdiocesan high school, affirms and believes. Yes, I have intentionally selected controversial issues, that is, issues on which opinions of many Catholics as well as non-Catholics have changed rather dramatically in recent years in a way that is at variance with Catholic teachings. These are the ones, then, on which we especially need to make clear that the institutional commitment of the archdiocesan high schools has not changed. In one sense, the message is simply that the teachings of the Catholic Church be accurately represented in the archdiocesan high schools.

Why is such clarity needed? The main reason is for the students and their parents. Many of our students need instruction in a Catholic plan of life. In addition, because they live in a secular society and are not yet sufficiently mature to critique it in important areas, they suffer from confusion on practical issues in life and society and don't understand how humility and chastity help them appreciate the teachings of the Church on these practical issues that greatly affect their wellbeing. By word and example, teachers have to do their best to bring about great clarity. It is also important to see that serious misunderstandings around these issues has caused unspeakable suffering to a whole lot of people.

I reassure you that I have provided adequate protections for teachers in our schools who have different views on a variety of doctrinal and moral issues. I have done this in two ways. First, at the beginning of the insert in the Faculty Handbook in the archdiocesan schools there are two paragraphs that acknowledge three groups of teachers in our archdiocesan schools. Some teachers completely endorse Catholic teachings and strive to live them as best they can with the help of God's grace. Not all of our Catholic teachers are there, and some do not accept all of the teachings of our Church. Still other teachers are not Catholic and yet make valuable contributions to our schools. Those teachers in a Catholic high school who differ in their private views from Catholic teaching continue to further the mission of the school when they avoid disagreeing with Catholic teaching in the classroom, in extracurricular activities, and in any public way outside the classroom.

Secondly, no teacher is being asked to sign a statement of faith or belief. No teacher has to change his or her beliefs. The belief statements that will be in the faculty handbooks begin with the phrase "we, the institution, affirm and believe." The point of these formulations is twofold. The first reason for the language is to signal to the outside world that, even as many people change their minds about traditional beliefs, the archdiocesan Catholic schools are still fully Catholic. The institutions still profess these beliefs. And the second reason is to alert teachers to the fact that these affirmations, which are related to hot button topics in secular society and in the Catholic Church, remain the teachings of the Catholic Church. Therefore, teachers in a Catholic school are not allowed to speak against these important beliefs in the school, nor are they allowed to act in a public way contrary to those beliefs, as this would compromise the Catholic mission of the school. Most teachers in our Catholic schools already behave this way. Inserting the language in the handbook is simply one way to memorialize the professional approach already taken by the teachers in our Catholic high schools.

V. Conclusion

A pithy way to sum up is as follows. In Catholic schools we teach virtue and truth, and we hold out holiness as the Christian vocation of all students. The core mission of the Catholic Church is to provide an integrated education to young men and women, that is, knowledge and virtue combined. The connections between the two are provided by Catholic practice and teachings. We believe this is the formula for outstanding schools, and for forming outstanding disciples of Jesus Christ. I am grateful to all of you for contributing to these lofty goals.

I know this can be difficult, I know it involves swimming upstream. Believe me, I know! There are some moments in life when our loyalties are tested. I would like, then, to leave you with a reflection, a Scripture passage taken from the Gospel of John, which are three excerpts from Jesus' farewell discourse to his apostles the night before he died. I think these reflections give us much food for thought at this moment of history:

This is my commandment: love one another as I love you. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one's life for one's friends. You are my friends if you do what I command you [Jn 15:12-13].

If the world hates you, realize that it hated me first. If you belonged to the world, the world would love its own; but because you do not belong to the world, and I have chosen you out of the world, the world hates you. Remember the word I spoke to you, 'No slave is greater than his master.' If they persecuted me, they will also persecute you. If they kept my word, they will also keep yours [Jn 15:18-20].

Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. Not as the world gives do I give it to you. Do not let your hearts be troubled or afraid [Jn 14:27]

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Archbishop Salvatore Joseph Cordileone. "Knowledge, Virtue, and Holiness." Address to Catholic High School Teachers Convocation, February 6th 2015.

Archbishop Salvatore Joseph Cordileone. "Knowledge, Virtue, and Holiness." Address to Catholic High School Teachers Convocation, February 6th 2015.

Reprinted with permission from Archbishop Salvatore Joseph Cordileone.

The Author

Archbishop Salvatore Joseph Cordileone (born June 5, 1956) is the archbishop of San Francisco, California. He chairs the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops' Subcommittee for the Promotion and Defense of Marriage. Archbishop Cordileone's avocations include a life-long interest in jazz music. Even during his seminary studies in Rome he played his alto saxophone in a jazz quintet, and continues to follow the music. He also enjoys swimming and spectator sports, especially professional baseball and football. He has not, however, declared his regional team preferences.

Copyright © 2015 Archbishop Salvatore J. Cordileone