On Moral Relativism

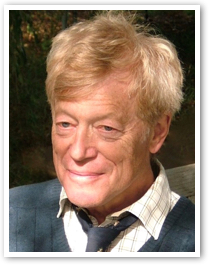

- ROGER SCRUTON

What, Roger, to your mind, is the problem with moral relativism?

Roger Scruton: Well, there is an intellectual problem as to what it is. What does a moral relativist believe?

Roger Scruton: Well, there is an intellectual problem as to what it is. What does a moral relativist believe?

He obviously believes that moral judgments do not have any kind of absolute force; but what follows from that? Are they relative to something? If so, to what are they relative?

That's one problem.

There's a huge discussion in the literature about this, a very inconclusive discussion.

The real problem is what it means to ordinary people, who don't have the philosophical training and philosophical inclination that some of us have, who nevertheless hear phrases like "it's all relative", "there are no absolute values", "any judgment you make is your judgment from your point of view", "there is no objective point of view".

These are all garbled versions of philosophical positions, but they are very influential on ordinary people and have given rise to the feeling that really in the end there is no point outside the individual's own perspective from which he can be judged. He can only be judged from within his own perspective, in terms of his own desires, ambitions, aims, and so on. Which means that judgment becomes a kind of impertinence and as a result of course, people cease to share any conception that they are joined in a common enterprise.

Interviewer: Maybe in just a few sentences, what exactly is moral relativism? Maybe you can put it in layman's terms. What's been its unique contribution to Western thought?

Roger Scruton: Well, I would say that in layman's terms a moral relativist is somebody who believes that a moral judgment is the expression of the subjective opinion of a particular person, and that it cannot be evaluated from any other position than his own.

So every judgment is relative to the interests and position of the person who makes it, so that in the end, there is no position outside the individual from which he can be judged.

Interviewer: So then maybe an older view of thinking of philosophy or approaching life would have been: an endeavor to discover truth.

Roger Scruton: Well, obviously one contrast with this is the religious world view which says there is a position outside the individual's interest from which he is judged. That is the position occupied by God, who as it were provides that overview, a systematic overview of all our desires and all our aims and is in a position to judge us. We can then by, as it were, discovering what His position is, come to an objective view of our own situation. And the obvious thing to say about moral relativism is that it's what is left when the religious world view collapses. And that's perhaps a reason why it's so prevalent now.

Interviewer: Do you have to have, though, a religious world view? Would an Aristotle have viewed it that way? Do you necessarily need to be religious to recognize that truth might exist and it would be worthwhile to discover what that is?

Roger Scruton: No, you don't, and of course that's been the effort of philosophy down the centuries (Aristotle is only one example, Kant another): to produce a fulcrum on which a worldview can turn which is not simply our own individual desires. I think for a long time after the Enlightenment, Western intellectuals believed that they'd discovered that in the idea of morality put forward by Kant or perhaps some version that was downstream from that, like the utilitarianism of John Stuart Mill and so on, which gave a secular grounding to a shared moral position which would not be the position of any particular person but the position of all of us; and from that we could come to conclusions about what was right and wrong which didn't privilege the individual and his desires.

But of course, I think there's been during the 20th century an increasing despair that that project was possible. And this despair had many forms, but one of the most important from the point of view of rhetoric was the existentialist position of people like Sartre. Sartre argued that there is no position from which I can be judged except my own, so that the only thing that can authenticate my moral judgment is my choice that those are my judgments.

So the difference between a moral and an immoral person on Sartre's view is simply that the moral person is somebody who wills his own desires as commitments, whereas the immoral person is someone who just has those desires. On that view, the authentic existentialist rapist is the one whom you should praise, not the person who simply is tempted by his sexual appetites.

Interviewer: So does the subjective understanding of truth, where I can't necessarily judge your value system or whatever else — we're told that this has led to an age of toleration, and yet a lot of those folks who espouse maybe a postmodern moral relativist view use the words "ought" and "should" and "must" quite a bit. How do we arrive at that sort of a didactic moral relativism?

Roger Scruton: It's a very good question, that. It's obviously a part of human nature to affirm ourselves through moral judgments. And when people adopt the view that all moral judgments are relative or subjective, they turn that into an objective morality too. So it becomes a kind of sin to be other than a relativist. And you see this happening especially in things like the European Court of Human Rights, where you find people with an old-fashioned objective system of values constantly being called before the judges and reproached for the fact that they are discriminating against people who don't share their values. It becomes ever more difficult to retain those old fashioned objective views of what morality is without being condemned on moral grounds for having those views.

So that kind of subjectivism becomes a moral norm, so it's not that people have given up on the idea of objective morality, it's that they're making a certain kind of subjectivity into an objective morality.

It's a kind of paradox and you see this paradox already in Nietzsche and people like that. Nietzsche affirmed something like a subjectivist view of morality, that what mattered, he said, "is to will your own desire as the law". It's your own desire and the will to power that's expressed through it that's the essence of the moral position. But of course Nietzsche very quickly turned that from a doctrine of liberation to a doctrine of condemnation.

Condemnation of all the people who couldn't live in that way and needed the support of an objective framework. I think you're finding that happening now in the kind of moralism that surrounds the European enterprise. I suspect that this becomes obscure because very often modern moralism clothes itself in the concept of human right.

The idea of universal human rights is a sort of political expression of the 18th century Enlightenment morality. Especially it grows out of Locke and out of Kant, and it is what we have retained in the modern world of that noble effort to construct an objective morality without God. And this morality had the form of respect for universal human rights that we all possess by virtue of our human nature and which we can affirm against each other. We can lay claim to them and expect others to acknowledge that claim. So it gives a fulcrum outside the individual desire on which the issue can be turned.

But it all went terribly wrong, in my view, after the Second World War, when people lost any sight of what the list of human rights consisted off.

Originally in people like Locke and also Kant, human rights are fundamentally negative things, a right not to be interfered with, not to have your life taken away, not to have your freedom taken away, not to have your property taken away, and so on.

Interviewer: And these would've been ideas that the American founding would've been rooted in.

Roger Scruton: Yes. Essentially liberal ideas, and it's sort of axiomatic in that way of thinking that "your right is my duty."

So if you have a right, I have a duty towards you to respect it. If your right is simply not to be interfered with it's easy for me to fulfill that duty: I don't interfere with you, don't kill you, take you property, enslave you, and so on.

With the universal declaration of human rights after the Second World War, all kinds of new rights came into existence — or they didn't come into existence; they were postulated by the process that then was initiated — including the right to have a job, the right to have security of home life, the right to have sufficient to cover the basic needs of existence, the right to health care and so on.

Gradually this list of rights expanded. These are not freedoms but claims. They're very different; it's not a freedom to go about your business undisturbed, but a claim that people are given against each other.

Interviewer: And that claim is rooted in what, a communal desire for ...?

Roger Scruton: At the time it was part of the whole move towards a more socialist conception of the state, because once you make these claims, if you hold onto the axiom that my right is somebody else's duty, you automatically have to answer the question: well whose is the duty to provide?

And of course it's not the duty of any particular person, it becomes the duty of society, which is another name for the state. It led to massive expansion of the states' embeddedness in human relations. Whether this was a good thing or bad thing is of course part of dispute in politics to this day, and it's one of the things which separated liberals from socialists.

But irrespective of whether you think this is a good thing or a bad thing, it clearly involves a radical change in our conception of what a right is. A right becomes a claim that we can each make against each other and of course then this tends to undermine people's sense that there really is any objective authority to the idea of a right.

When somebody comes along and says to me he has a certain claim against me even though there is no relationship, I tend to think of that as nonsense. This confusion about the idea of human rights means that there's a considerable amount of nonsense embedded in our legal systems.

Interviewer: In a political order sort of founded on this idea where rights are sort of dictated or coming from the state, if you felt like you're a victim of nonsense, what can you appeal to?

Roger Scruton: It's a very good question. People… There's… Let me give you an interesting case:

In my country we have a very important tradition of planning law which arose between the wars and was solidified after the 2nd World War, according to which you cannot build houses in the countryside. Not without very special permission, because people valued the countryside in — as you know — an overcrowded island, and wanted to preserve it. This law creates certain duties on the part of the citizen to obey it — not to build anywhere, anyhow. And people accepted it as a piece of legislation. It doesn't talk about anybody's right; it just talks about what duties are under the law.

But then Irish travelers enjoying freedom of movement under the European Union laws, come and settle in our countryside with their caravans, scraping away the top soil, putting down concrete and littering the place with these what Americans would call trailer parks.

And then, of course this is against the law, but they appeal to the European Court of Human Rights, saying "we have a right as an ethnic minority to live in a traditional way, and this is our traditional way".

Now, if the court upholds that judgment, and says they do have a right, then all other interests are canceled by it, because a right is a non-negotiable privilege. Whereas the neighbors of these people just have whatever ordinary legislative rights and duties have been laid down. So, the result is that this law is no longer applicable. One thing that happens as a result of that of course is social tension. Indeed, we've had a couple of murders in one of these camps as a result of this. And people mostly who don't accept the fact that they having obeyed the law to maintain the beautiful environment in which they were can see it just taken away from them by people who don't have to obey the law, because they can overreach it through these international courts.

But increasingly that is happening, that overreaching of the law, through the doctrine of human rights and through these claims that people make — claims to lifestyle and so on.

Interviewer: You are suggesting that there really is nothing to appeal to once you reach a certain state?

Roger Scruton: Well, this is a technical problem, but in our law, and I think in all laws, if something is a right attaching to an individual, then that's it. The judge is obliged to grant it. There can be conflicts of rights, but you see, the neighbors of the travelers, in the case I am considering, didn't have any rights in the matter. They just had interests, so the courts had no way of judging in their favor.

Interviewer: But often laws are made with interest in mind.

Roger Scruton: Oh yes, and that's the whole purpose of legislation: that it tries to take all the interests into consideration and find an acceptable compromise solution. That's only one example that I took, but there are plenty that are much more relevant perhaps to life in this part of the world, although I suspect the European Court of Human Rights will certainly upset relations between Hungarians and Roma in this country by overriding settled ways of dealing, and you might have the same sort of problem.

But more important are things like the conflict that arises between the Catholic worldview and this new concept of human rights. Catholics have always said, "We were the true originators of the human right idea. Look at Saint Thomas — it's all there: the concept of natural law and upholding human rights and that believing indeed that there is this universal jurisdiction which is God's. But these rights are not for us to determine according to political criteria or according to the desires of people in secular society, they are eternal."

You know, for instance, although there is a right to life, the Roman Catholic would say that right attaches to the unborn too. To the child in the womb. And the European Court of Human Rights will say no. Because that interferes with the right to abortion that we guarantee, because it's part of what is offered by way of settling disputes in a secular society. The Polish government has had to confront this, and I'm not sure that it's resolved it yet, as to whether it can change, whether it is going to change, its law on abortion or not.

Interviewer: So you seem to be suggesting that the phrase "different strokes for different folks" sounds all well and good, but in fact when you have such radically different ideas about justice and life and truth, and you have to build a society or life, and make laws, have neighbors, that it actually can be an impediment and may actually not lead to toleration.

Roger Scruton: Yeah, we got off the concept or topic of toleration. The influence of moral relativism is to say that it's intolerant to make judgment at all. This is what we find often said in my country, that someone being judgmental is committing primary moral fault. And real toleration means not discriminating at all against rival views — accepting all views as equally valid.

But actually, toleration means the opposite of that: toleration means accepting what you don't approve of, or accepting what you do disagree with. Our tradition in England of toleration, which grew out of the 17th century, was a solution to radical conflict.

People learnt to be tolerant precisely of the things they really hated. Learning not to hate them means not tolerating at all, because there's nothing to tolerate. And this is a very important virtue in this case, toleration, but it depends upon having objective moral values.

Interviewer: So in that sense toleration, the way we might understand it today, is actually quite a bit different than the Christian concept of brotherly love or the golden rule.

Roger Scruton: The Christian concept of brotherly love means loving the sinner and hating the sin. That's a very different conception from the modern version which is more like: loving the sin and not regarding it as one.

Interviewer: Before we turn to questions from the audience, lets discover what the absence of truth claims or making judgments means in other areas of life. You've written that in art and architecture — in art the original idea was to try to point the viewer of that sculpture or that painting towards some sort of higher plane, towards a closer realization of some sort of truth. In architecture of course, the main idea was to create structures that were to be inhabitable for humans, to live or to work in. Has that changed?

Roger Scruton: No. It's much more difficult to defend some kind of objective aesthetics than it is to defend an objective morality. In the end, once you stated questions of morality clearly, an awful lot of it is plain common sense, as the name of your Society commemorates.

But plain common sense about art is quite difficult to obtain. In fact, it seems to me architecture is the only clear example in which people do spontaneously agree with each other. Everybody, that's to say, except architects, and that's because architects make money out of it. And I think you will find that, certainly in the European context, there is a natural tendency to accept certain forms and reject others, accept forms which give the air of a settlement, a place where you can be at home, and that architecture is touching on something which is deeper than aesthetics, which is our need to settle together as communities. And from that need follow things like the shapes of windows, the shapes of roofs, the height of buildings. And even things like details, you know, shadows. You can't live in a building, you can't look at a building, which doesn't have shadows. There's one over there which has none, which is kind a glazed monstrosity like a big eye looking at the people of Budapest and defying them. You know, it's not something in the vicinity of which you can actually feel at home. That's part of its purpose, because it's there to sell things, not to soothe people.

But I think in the sphere of architecture you can draw on other things than the pure look of buildings, in order to establish some type of consensus, and it's very clear from the cities of Europe that that consensus has existed for at least 3000 years in a very broad sense: the column and the architrave, and the roof and the window. These are standard things. When it comes to music and painting, things look a little bit different but still, there's an expectation in most morally alive people that art should not, as D.H. Lawrence puts it, "do dirt on life." It shouldn't desecrate the ordinary expectations and the ordinary modes of fulfillment that people have. You know — obscenity, destructive violence, chaos — works that rather seem to celebrate the negative. For that reason I think, it puts people's teeth on edge and also gives them a sense of sacrilege sometimes, and working out that idea is one thing to which I've devoted some of my work, so I have a few things to say about it.

Interviewer: Let's open it up for questions

Question: What's your opinion about human rights organizations that enforce their own agenda upon nation states?

Roger Scruton: I think that these international human rights organizations are — part of the problem with them is that, as you imply, the agenda has grown uncontrolled, so we don't really know whether there is a human right to social welfare, is there a human right to a roof over your head, or a human right to health? What would settle the question? Nobody knows. I can obviously claim that I have a human right as a red-haired person to special privileges when traveling in places like this where there are so few of them. And people do, but most people would laugh and say "No, that's ridiculous."

But nevertheless, what are the grounds? Nobody knows. That is part of the problem, there is an attempt to produce a kind of universal objective morality but without any conception of where it comes from. The idea that people can't be judged in their own cause of course is universally accepted only because everybody has an interest in their own cause other than its justice. The fundamental idea of natural justice, at least in English law, is that a dispute between two people must be adjudicated by a third person who has no interest in either's side. If you have no interest in the matter, only justice can motivate your decision; that's the idea.

Question: Is it problematic that sometimes these human rights organizations seem to not care about persons, but about their own special interests?

Roger Scruton: It is problematic. They have political agendas and all that, of course, and they get taken over by people who have a decided desire to reform whole societies. I mean the European Union, or the European Commission, is very much characterized by this. It is staffed by people who belong to essentially the transnational rootless elite who don't actually have very many beliefs of a traditional kind and are extremely irritated by the spectacle of a place like Poland and a place like Hungary. I mean there's lots to be irritated about Hungary no doubt, but you know the European Commission is the first to be irritated, and will have reference to these vaguely defined human rights in order to make its position known, and that of course can produce enormous resentment. It has produced resentment, certainly in my country and in Poland, and will go on doing so.

Interviewer: Let me ask another question. You're talking about the EU. So in the European Parlement, I think not long ago, there was some sort of decision made that you couldn't use gender distinctive terms in the documents, so no Monsieur, no Madame, no Fräulein, whatever else. Of course we know there are now folks who think of sort of different layers of gender: you can be male bodied or female bodied, which is an anatomical thing, as opposed to your identity, which would then be male or female. So, does this idea also originate in that gender is not something you can observe with a rational mind, and sort of know what it is, but that it really is about your identity, your judgment of yourself?

Roger Scruton: Well, yes. This is another issue, it's very easy for these transnational institutions like the European Parliament to respond to pressure groups of small organized people, obviously radical feminists from France in this particular case. And those people probably wouldn't be able to force their views upon the whole public of France through the normal democratic process because then they would come up against the fact that the French people don't want to lose Monsieur, Madame, Mademoiselle and so on. This is one way in which elites impose their views on majorities, by using these roundabout transnational institutions, although in American elites use the Supreme Court in the same way to bypass ordinary people's feelings. This has been obvious in the case of abortion — that the standard New York liberal position on abortion was made into a nationwide orthodoxy through the Supreme Court. OK, it's moving back the other way but that's something that just does happen.

Many people say: "Listen, what does it matter whether we drop the word Monsieur, or Madame or whatever," but it's a bit like what happened in Turkey in 1919-1922 I think. When Ataturk said, The Turkish language must no longer be written in Arabic script, it's got to be written in Latin alphabet, that's much more sensible and straight-forward, and then it'd be much easier for people to learn it from the Western countries, and we can relate to western countries much more easily. And it had a fantastic effect, it changed Turkish society in a radical way, but it cut Turks off completely from their literary past.

Nobody in Turkey today can read any of the classics, except a few, you know, highly educated people. Maybe that doesn't matter because the classics weren't any good, but I don't think that is true.

But in a similar way, but less severely, American feminism, which is insisting on the feminine pronoun, is cutting off many people from the natural sense of the rhythm of English as used by those, you know, reactionary writers like Hume and Burke and even John Stuart Mill.

Question: One of the basic assumptions of conservatism is that each community has its own way of settling problems and its own morals. Isn't that another form of moral relativism?

Roger Scruton: That's a very good point, I think. I don't think I've succeeded in defining moral relativism because I think it's so elusive a thing, one might say that a certain kind of conservatism says that custom has a validity of its own, which is what you're saying is very appealing, but it isn't a form of relativism, because it is actually validating custom as such, saying, you know, custom does have a value. And it stacks the way we look for solutions, and these solutions have emerged from people's interactions over generations and that's why we should respect them. This is something that Burke said in his Reflections on the French Revolution, and really he was speaking about a very objective moral truth — that the answers to social questions are not invented but discovered, and they're discovered over time, through the people's interaction.

Interviewer: But of course, different people don't discover them, and maybe have bad customs. When for example, noticing these differences among people, I guess is as old as history. Herodotus famously noted differences in some of the African tribes and in Eurasia. So, how do you then treat different customs if you recognize them to be somewhat morally different?

Roger Scruton: This is what the Enlightenment wanted to do. Which as I've said was to find that position outside specific customs from which they could all be judged, and the universal doctrine of human rights was supposed to be that position. And my view is that perhaps it is, as long as rights are treated in this purely negative way that the American founders treated them and as Kant treated them, and really as Aquinas treated them. But when the doctrine of human rights starts escalating without any grounds, then all you're doing is imposing a new elite morality on people who can't possibly accept it. But, there are problems, as we know; most of us feel that there are aspects of many of the Muslim societies that we're becoming familiar with these days which we can't accept.

You know: forced marriages, honor killing, even perhaps the constant concealing of women; to us that is repugnant, but you know, there is a question in many peoples mind: If you then just impose the Enlightenment liberal morality on these communities, are you doing them a service or not? There is a real conflict here, a conflict of values.

Interviewer: But of course, some of our customs they probably also think are repugnant, so then what are we to do?

Roger Scruton: Well, the answer was, you know, to send them back home, but you can't say that. You have to say, no we've got to live together as communities and they are right to be repelled by, you know, pornography and all these things they are repelled by in our communities, and we're right to be repelled by their treatment of women, and an accommodation over time might improve both of us.

Interviewer: On this same topic, in England, is the acceptance of certain forms of sharia law within the British legal system a sort of a natural outgrowth of our wanting to treat their understanding of justice as similar, as equal to, ours and somehow compatible even in the same nation?

Roger Scruton: No, because, our nation is founded upon the rule of law, and this law has always been secular, and what the law is, is settled by a parliament and by the courts in obedience to parliament. So to say that there should be a sharia law adjudicated in parallel is effectively to deny that there is a unified nation. The Ottoman empire lasted in this way quite for a long time, saying family affairs are adjudicated by sharia if the family is Sunni Muslim or by the canon law of the Catholic Church if there Maronite and the orthodox jurisdiction of Athens I guess for the Greek Catholic and so on. And they managed it, but they managed it only because there were no nations. It was an empire without borders. We have the view that the ultimate source of authority is the nation state, defined by its borders. And within those borders, the law, the secular law as determined by Parliament, is the final authority. That's not just an arbitrary thing for us, that is the foundation of our obedience. If a community grows up within those borders not accepting that, then it doesn't belong within those borders and there's no other solution.

Interviewer: So by endorsing parallel legal systems they are in fact rejecting…

Roger Scruton: …the nation state.

Question: At which point does a nation state's legislation become unacceptable?

Roger Scruton: It doesn't follow from the fact that our obedience is to the rule of law that the law can just be anything — there are internal constraints. Not only the constraints of democratic election to parliament, but the constraints of constitutions and of procedures embedded within the law.

And the problem with Carl Schmitt, one of the many problems with Carl Schmitt, was that he had this kind of extremism of the time, of those terrible years between the wars where he just wanted to put a guillotine through everything, and say: at a certain stage it stops, you know. And he says: "he is leader who has the voice in, the final voice in, a crisis". For him the crisis is what settles who is in authority. We English always had the opposite view, that in a crisis, that's when you should look for the authority that has come about in peacetime. It's not the crisis that settles who is in authority, but the normal peaceful dealings between people when there is no crisis. The whole purpose of politics is to avoid crisis. On the whole we English do avoid them very well; that's why we seem so complacent. I think that the same is true here — that if you look back on people like Kelson and so on, and the Austro-Hungarian tradition, although it's very different from the English, it is talking about the normal way of dealing with things and not the crisis.

Question: If everybody has the right to decide which way to live and that it should be respected, isn't this a kind of moral relativism too?

Roger Scruton: As I understand it, the Enlightenment conception of — well, there is no one Enlightenment conception — the Enlightenment conception that the American constitution embodies tries to set the state up as the thing which settles disputes, the thing which maintains the ongoing peaceable communion of people, and represents their interests in the world as a whole. Which means it doesn't in itself dictate to them all the axioms which they will need for day to day living.

There is also this whole sphere of human life, in which morality and religion play their part, but those spheres are not in themselves the sphere of the political, so there is a separation of the political sphere from the moral and certainly from the religious, obviously famously so in the American case. It doesn't mean that the state doesn't in some oblique way depend on those spheres — that if people become completely demoralized and completely lose all religious sense then of course it could be that the state also suffers from that; it's no longer able really to rely upon customs that it needed to rely upon in order to function, and I think that might be true.

Question: What is a successful strategy if one wants to restore some kind of moral order in our societies while at the same time avoiding accusations of fascism or being a bully?

Roger Scruton: Humour is very important, also satire of the opponent, you know. It's very difficult because as I was saying earlier, moral relativism has a tendency quickly to become a kind of absolutism of its own, you know. So that if you're making judgments or if you're revealing that you have some source of values which you regard as sacred or holy, or outside of this personal choice, then people do start abusing you and that's undeniably true. But in the long run, you know, you can stand up to that and things change. People might abuse you for a, as a fascist or whatever for 10 years, but you know when the results of their worldview are being felt all around them, they might come back to saying: "You know, she was right all along", you know. And that's, I mean, to a very small extent I've had this experience. I was, when I started coming out as a conservative round about 1980, it was to the immense shock of the academic establishment and I had to sue people for lible for things that were said.

There was a BBC programme with the sound of marching jackboots behind, you know, somebody commenting on something I'd written. Everything was done to make it look as though this was the thin end of the fascist wedge. For a long time I was very disheartened by it, you know, and you can feel very distressed, but things have changed now and a great many people think that possibly I wasn't totally wrong about everything and a sudden rehabilitation comes about, you know. I was sort of kept out of the British Academy, for instance, by all the old left establishment: Fallheim, Williams, Isaiah Berlin and all that crowd, and then they all died. I have to say I was out of the country at the time, had nothing to do with it; they just died and the next week I was made a fellow of the British Academy. So that's a sure sign that perhaps things do change.

Question: If we agree that there is a settled moral absolute, doesn't that still leave a lot of space for certain moral questions to be a matter of convention and to be decided differently in separate communities?

Roger Scruton: That certainly is true. Obviously, we all have plenty of examples like just basic human relations; families are differently constituted and yet can live side by side, although you know, still there might be a question of whether you have to be tolerant in order for this to happen. And toleration means perhaps accepting that your neighbor isn't living in the right way, but nevertheless it's not for you — you have no right to interfere. And that's a very normal position to take I suspect in Western societies. And we don't go through life thinking that every question is to be settled by a moral absolute; I mean we are negotiating creatures and that's especially true of us Europeans because our systems of law emerged from negotiations; they're not dictated from on high by God, unlike the Sharia. They are the results of discussion over many hundreds of years, even in the English case a thousand years, so we're used to the idea that we don't settle all our questions by moral absolutes, but still we might need some of those absolutes in order to begin.

Interviewer: It seems to me that maybe the worst outcome for a society that completely embraces moral relativism is just a reassertion of the idea that might is right, and sort of power of politics. Do you agree with that or is there a worse outcome?

Roger Scruton: This is a quite interesting point, in the 1960s, when the — I wouldn't say the fall of man began then, but nevertheless things did change, in a radical way. Very popular at the time was not just the relativistic morality of the student revolution, but the philosophy that rewrote morality as a system of power. Foucault was the most important person in this, and the basic argument in Foucault's writings, and it's an argument which comes ultimately from Marx, is that moral judgments have no intrinsic validity. They are part of ideology, whose reality has to be understood in terms of the power relations that they vindicate or endorse.

To know what is being said by a moral judgment, you must go behind it to discover the relations of power which are being concealed by it, made to look legitimate. Once you think like that, you think that you have an absolute right to overthrow those relations of power because they have no ground other than themselves, and with them overthrow the morality that goes with them.

In Foucault's four-volume Histoire de la Sexualité, which I'm sure some of you know, you will discover this all at work: this overthrowing of every possible system of sexual morality as a mere legitimization of power relations in particular historical context, and that's being very influential of course on adolescent, on the sexual behavior of half-educated adolescents. Not fully educated or completely uneducated, but the ones in between. And Foucault of course is a very important thinker in that he sort of made the postmodern world through this kind of way of thinking.

Question: Hungary grapples with a two-fold problem: the moral damage brought on by communism and the current prevailing relativism of the west. So what is the way forward for Hungary?

Roger Scruton: Well, I understand the problem because obviously it's being talked about everywhere and in particular the Hungarian situation. My view is that one should not look for political solutions to this, the problem that we've been discussing today. We're talking about something that goes to the heart of personal life and personal relations. It's as though the Enlightenment is finally come home to us and what it means to us. And we, many people, feel that there is an urgent need, a worldwide need, to find some other foundation for the moral life than religion.

Now I, I'm skeptical that there really can be that other foundation, but certainly it can't be politics. One of the problems with communism is that they did try to provide an alternative foundation not just for political order but for the moral life, and to recruit everybody to a kind of militarized equality, which people have rejected because they've seen that it disenchanted human society completely, left people demoralized and in opposition to each other about everything. Harmony can come about; however, not through politics. It can only come about because people recognize the value of their own life and the value of the life of those around them and that's something that has to be created through their own efforts.

Interviewer: In America, in a book called The Closing of the American Mind, the author talks about some of the effects of what you have mentioned: the pessimism and the skepticism, the dismissal of truth claims that came out of the 1960s. He talked about it in the context of the university, such that the students don't inquire after knowledge or seek after truth anymore. He made a rather outrageous statement that he saw somehow a worse situation than even, maybe religious wars that were happening in Europe. Do you think that's a little far-fetched or is he trying to get at something that, you know, possibly embracing that sort of moral relativism and it eroding the foundations of justice or those laws we've talked about previously in the case of Britain somehow has a deadly effect on civilization on the long run?

Roger Scruton: Yes. Well, there is a tendency of people in universities to think that what's going on in the university is what really matters and that was the case of Bloom. When he was talking about the closing of the American mind, he really meant the fact that he couldn't talk to his students anymore. Outside the universities there are all kinds of natural, normal Americans still existing, going about their business, going to church services. America has remained a devoted, devout Christian society through all these things — at least, if you're outside the cities and also if you're outside the universities, a basically decent society. So the fact is that it wasn't as bad as he thought, it was just bad for him. But he had a point because what he was saying was that relativism had made it impossible for him to teach the curriculum as though it had any objective authority. That was really what upset him. You couldn't really say to the student, here is Shakespeare, just look; here is Steinbeck, just look. Surely you've got to see that that first thing is not just better, but touching on the human reality in a deeper way. And his students would say: "That's your view, I've got my Bob Dylan" — which is a million times better than what they have now. There is a problem if you can't teach the old curriculum in the humanities because of this relativism; what are you going to teach students? Increasingly, people teach pseudo-sciences instead: the deconstructionist analysis of Steinbeck. Or instead of teaching esthetics, neuro-esthetics — not knowing quite what that is, except it's Beethoven plus brain scans.

Interviewer: Is, after all, moral relativism that big of a problem? If it only amounts to difference of opinions and occasional renegotiating of the political structure, is it really that big of a problem?

Roger Scruton: I would say that we have to be much more careful of our institutions than moral relativists tend to be; our values as Europeans come about through long standing institutions. Here, as the gentleman said in the back, communism destroyed the institutional superstructure, but it needs to be rebuilt. And the example of Bloom — The Closing of the American Mind — is significant, because it has become difficult to maintain the dignity of the university in the times in which we live. Churches have found it extremely difficult to maintain their teaching when anything goes, and traditional marriage upon which the reproduction of society depends, as we all know, is under threat throughout the western world as some supposedly arbitrary agreement between two adults to share each other's — or, as Kant said, a contract for the mutual use of the sexual organs. Kant's view — Kant was obviously quite repelled by marriage as you can imagine, but that's the view that is prevailing and of course it leaves children out of consideration. Once you've left children out of consideration: things have come to an end. They haven't yet though; I've got two.

Interviewer: Thank you all for coming tonight, please join me in thanking Roger Scruton.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Roger Scruton. "On Moral Relativism." A conversation with Roger Scruton at Café Gerbeaud in Budapest, Hungary. (January 25, 2012).

Roger Scruton. "On Moral Relativism." A conversation with Roger Scruton at Café Gerbeaud in Budapest, Hungary. (January 25, 2012).

This article reprinted with permission from Roger Scruton.

The Author

Sir Roger Scruton (1944-2019) was a philosopher, public commentator and author of over 40 books. He is the author of Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition, On Human Nature, The Disappeared, Notes from Underground, The Face of God, The Uses of Pessimism: And the Danger of False Hope, Beauty, Understanding Music: Philosophy and Interpretation, I Drink therefore I am, Culture Counts: Faith and Feeling in a World Besieged, The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought, News from Somewhere: On Settling, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Modern Culture, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Philosophy, Sexual Desire, The Aesthetics of Music, The West and the Rest: Globalization and the Terrorist Threat, Death-Devoted Heart: Sex and the Sacred in Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, A Political Philosphy, and Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life. Roger Scruton was a member of the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Sir Roger Scruton (1944-2019) was a philosopher, public commentator and author of over 40 books. He is the author of Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition, On Human Nature, The Disappeared, Notes from Underground, The Face of God, The Uses of Pessimism: And the Danger of False Hope, Beauty, Understanding Music: Philosophy and Interpretation, I Drink therefore I am, Culture Counts: Faith and Feeling in a World Besieged, The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought, News from Somewhere: On Settling, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Modern Culture, An Intelligent Person's Guide to Philosophy, Sexual Desire, The Aesthetics of Music, The West and the Rest: Globalization and the Terrorist Threat, Death-Devoted Heart: Sex and the Sacred in Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, A Political Philosphy, and Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life. Roger Scruton was a member of the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.